introduction

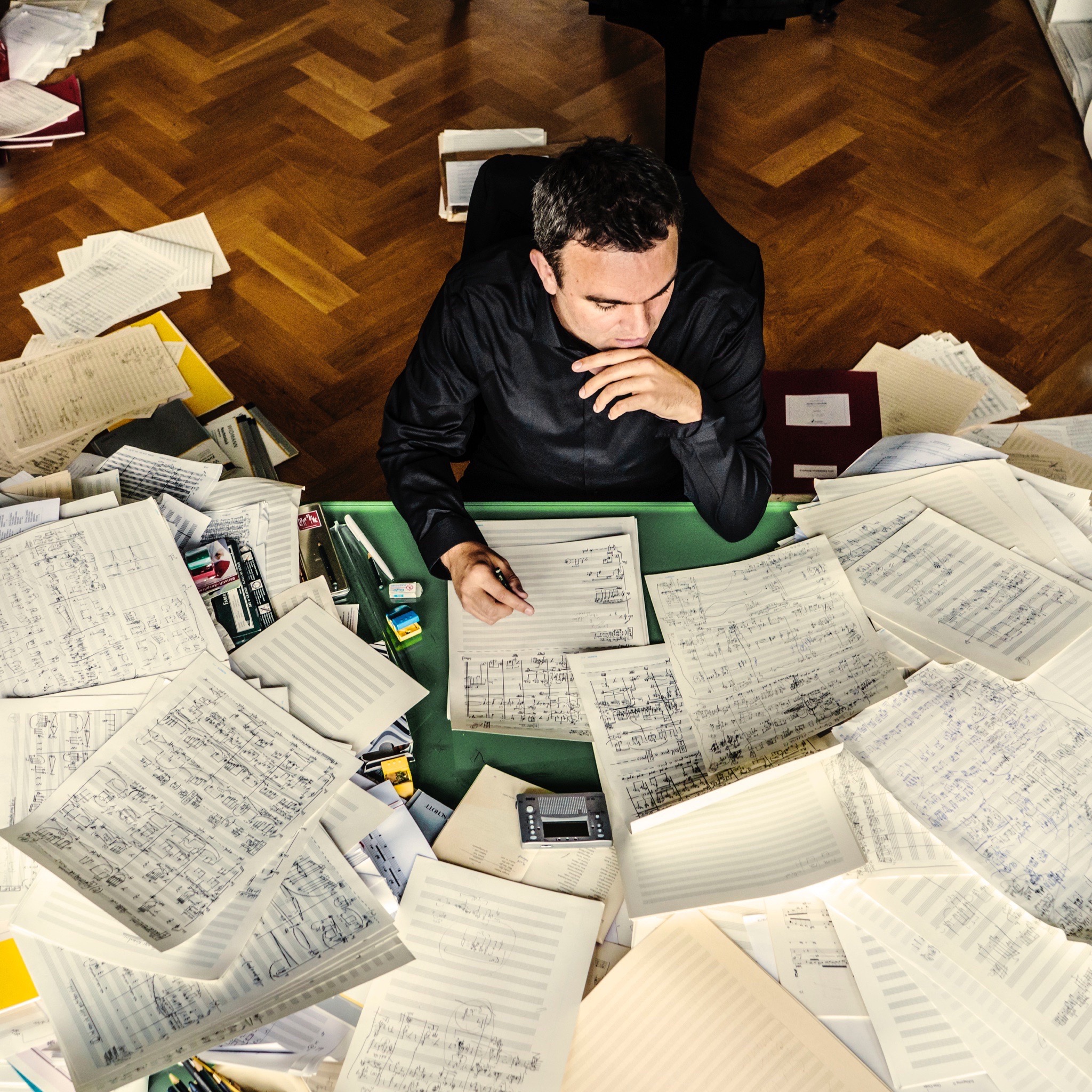

Adam Szabo

Artistic Director, Manchester Collective

It's funny how these shows come together.

More than eighteen months ago, when Rakhi and I were first putting together a draft of what would later become the Manchester Collective 2017 Season, one of the first things that we discussed was that we would love to have a string quartet programme as part of our lineup of shows.

I had recently performed and fallen in love with "Babylon-Suite", a condensed orchestral version of Jörg Widmann's 2012 opera, "Babylon". My discovery of this work - it has to be said, by 2012 I was pretty late to the Widmann party - led me down a rabbit hole of other fantastic compositions by this man, who I believe is one of the most brilliant living composers we have today. Finally, I happened upon his cycle of string quartets, and then upon the work we are to perform today - the "Hunt Quartet", or, in the original German, "Jagdquartett". Immediately, it felt like a perfect fit for Manchester Collective - incredibly dramatic, musically superb, and unbelievably unsettling.

"The Hunt" is not an easy work to listen to. Nor, for many, is it particularly "enjoyable", at least not in the conventional sense of the word. It's a piece that forces the listener to look into the abyss - to acknowledge that darkness and violence are as much a part of our world as light, joy, and inspiration. I still find myself tensing up every time I hear it in performance, and in a world where so much of the content that we consume is simply "meh", I think it's incredible that a twelve minute long piece of music written for four string instruments can elicit such a strong reaction. It truly is a tour de force.

We were originally going to pair the Widmann with another "Hunt" piece - Mozart's gorgeous String Quartet K.458, also titled "Hunt Quartet". In the end though, we felt the symmetry of Mozart - Widmann - Beethoven was a little... too comfortable. So it was that we ended up with Philip Glass' magnificent "Buczak", another work about the end of a life.

The other essential ingredient in our first pure string quartet show was always going to be one of the Beethoven late string quartets. Mr Beethoven's Op. 131 is undoubtedly a high-point of the quartet repertoire, and is one of the most musically and technically demanding works that we will perform in 2017. Between this epic work, Glass' meditative ode, and Widmann's mad rush to the finish, THE HUNT covers an incredible breadth and variety of music composed for this rather special lineup.

We hope you enjoy the show. We have certainly enjoyed bringing it to you.

listening guide

glass: String Quartet No. 4, "Buczak" (1989) - 24 mins

I. Untitled

II. Untitled

III. Untitled

Can instrumental music describe something specific?

How can a string quartet be about one man's life?

Can music tell a story?

Painting by Chuck Close. Phil, 1969, acrylic on canvas

In 1988, the artist Brian Buczak died, succumbing to a long battle with AIDS. The very next year, Philip Glass published his fourth string quartet, a memorial work celebrating the life of Buczak.

The first movement of the piece opens with a grand gesture. We hear ten chords, each chord a whole bar in length, that act as a sort of harmonic prologue to the movement, describing some of the sounds to come. As soon as the chords are over (you may well hear them twice - at the time of writing, we still haven't decided whether to include a hotly debated repeat in this passage), we launch into a rippling passage of quavers that form the bulk of the work.

Philip Glass is one of the American Minimalist composers - composers characterised by their use of small musical cells, like sonic lego blocks, to build up a large texture. Through the "Buczak" Quartet, the constant rippling sound of quavers is never far away. A neat trick to get into the piece is to listen to and follow these fast notes - they are regularly passed around the group, bounced from player to player.

In the second movement, we start to get an idea of how this quartet might be about death, or at least, transition. Here, the music takes on a more melancholy, reflective tone. In the viola and the cello, an oscillating figure is slowly repeated, like a gentle flurry of fallen leaves, while the violins float a spare and cold melody over the top, first in unison, and then in canon. Finally, the cello repeats the tune, but this time in a more optimistic, major key. The positive energy however, soon dissipates, and the music stops.

The last movement is reflective and simple - Glass uses an undecorated scale, first in the violin and then in the cello, as the main melodic material. The rippling quavers are back - gentle and unthreatening, but inevitable. There is very little variation in tempo - Glass paints a quiet, meditative picture of a man who is gone from the world.

widmann: String Quartet No. 3, “Jagdquartett” (2003) - 12 mins

Marco Borggreve, 2015.

"When I was little, one of my musical professors taught me I had to be like an actress when I was performing. At the time, I did not quite get his point, or I was too timid to behave as he said. However, now I believe it is true.

The piece we perform - “Jagdquartet” by Widmann - is one of the works for which I feel we need to be totally like actors. This work has got tremendous excitement.

I feel as if I fall into a trance when I am playing the entire piece, which can be absolutely dangerous! I am sure this magnetic, mysterious power will bring our audience into Widmann's vivid world, until the prey is completely caught in the end."

- Violist, Kimi Makino, on "The Hunt"

This is a piece about destruction. Not slow, eroding, global warming, passing of time destruction, but active destruction. Widmann begins the work with a snatch of music by Schumann and a classical, obsessively dotted rhythm, and then systematically dismantles the sounds we recognise until there is nothing left.

The "Hunt Quartet", terrifying though it is, is tremendously engaging to perform. Widmann gives the musicians plenty to think about, cramming the parts full of techniques and sounds that one might not normally hear from a string quartet. Before the "music" itself even starts, he instructs the quartet to swing their bows through the air at top speed to create a whooshing sound, like arrows whistling through the air. Things only get more strange from there - the musicians shout, pluck, grind, hit the strings with the bow, play on the wrong side of the bridge, and generally make the sorts of sounds that would get you sent out of class in music college. The composer goes so far as to mark "immer hässlich" - "always ugly" - in one corner of the cello part.

In the forward to the work, Widmann describes one idea he had during the compositional process: that the music behaves as a kind of aural metaphor for a society tearing itself apart. At the outset of the work, the voices in the piece speak in unison and in harmony, but before long, the protagonists turn on each other with brutal consequences.

There is however, a glimmer of hope. Widmann also describes "barely being able to disguise" his own excitement and earnestness during the writing of the piece. While we may have to struggle through Widmann's sonic whirlwind, at least we can rest in the knowledge that one of the parties involved was having a good time.

"At first glance the score of the Hunt looks like a dense bramble of detailed articulation markings and complex rhythms, and I did sort of wonder where to start in terms of interpreting it!

Strangely, as soon as we started putting it together, the jagged sound world and dark theatre of the piece seemed to emerge on its own. It's an incredibly visceral experience playing this music. As an instrumentalist, I don't get to use my voice while I'm playing very often, and to use it in such a crude, bloodthirsty and ultimately (for my part) life or death way is incredibly intense."

- Cellist, Abby Hayward, on "The Hunt"

beethoven: String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131 (1826) - 39 mins

I. Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo

II. Allegro molto vivace

III. Allegro moderato – Adagio

IV. Theme (Andante ma non troppo e molto cantabile) and variations

V. Presto

VI. Adagio quasi un poco andante

VII. Allegro

Beethoven for Prez

The six late string quartets by Beethoven represent perhaps the most extreme development in form of the "classical string quartet".

We should clarify - this is not an attempt to throw shade on Haydn, Mozart, and the rest of the classical crew. The quartets written by Beethoven's predecessors are no less beautiful, however, they are undeniably more well behaved. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the classical values of symmetry, elegance, and simplicity cast a long shadow over the quartet scene. Ludwig was the one that reinvented the form.

It's hard to overstate just how bonkers this piece is. (As we said of the Widmann earlier, it's exactly the sort of work that would have gotten you thrown out of composer class in 1800).

For a start, Op. 131 is in seven movements - this is incredibly unusual. In this quartet, the central (fourth) theme and variations movement forms the beating heart of the work, flanked by three movements on either side. Secondly, the music is incredibly dramatic and theatrical. Beethoven refuses to pick a melody and simply develop it over the course of a movement, instead, we get new material being introduced the whole way through, and rhetorical "storytelling" passages straight out of the opera house.

The first movement opens with an incredibly strange, lost sounding theme in the first violin - four notes that seem at first to be totally unrelated. Beethoven treats the theme as a fugue (passing the same material around the string quartet, until four voices are playing in counterpoint with each other), but the ground is always shifting underneath. As a listener, you never quite feel at home - Beethoven keeps us in a state of harmonic uncertainty the whole time.

The second movement is generous and bucolic, a total contrast to the tightness of the first movement. The constantly flowing melody bubbles along relentlessly, albeit with occasional rude interruptions. (The fictional listing on Amazon for this movement would probably read: "People that bought this also bought Mendelssohn Octet or Beethoven Pastorale Symphony").

We are brought back to reality with a bump in third movement, a short and highly dramatic recitativo. Here, there is no repeated material, and the music is allowed to adopt the rhythms of ordinary speech. It sounds a little like an argument, and it launches us swiftly into the fourth movement.

As the Andante of the fourth movement begins, listen carefully. The music sounds almost like a prayer or an anthem, and this extremely simple and chaste theme forms the musical basis for everything that is about to unfold. This movement takes the form of a theme and variations - Beethoven is able to show off his skills as a masterful manipulator of musical material. The anthem tune is always buried somewhere, but it never quite sounds like the last time.

The fifth movement is an exuberant scherzo - incredibly fast and technically demanding, and a whole lot of fun. Listen out for the outrageous plucking that interrupts the flow of the music again and again as it winds itself up to a manic conclusion.

We have moment of brief respite in the sixth movement - a deathly soft movement that perhaps foreshadows the famous Trio: Andante Sostenuto from Schubert's String Quintet in C Major, written just two years later.

Finally, we close with a movement that is perhaps the stormiest of everything that we have heard. Crazed dotted rhythms dominate the texture, recalling the last movement from Schubert's Death and the Maiden, written just two years earlier. (Is there an echo in here?). A huge ending to a huge quartet.

"For me, the string quartet is the ultimate way to make music, and that’s probably down to the fact that through it, we get to play some of the most amazing repertoire ever written. Tonight, we will show you a little drop from the vast ocean of that repertoire, but boy will we take you on a rollercoaster of a journey.

It’s quite hard to put in to words how it feels to play a masterpiece such as Beethoven Op. 131. There’s something his music that is so raw and full of human emotion that even rehearsing it is an incredibly moving experience. There is only one word I can use when trying to describe Beethoven’s music: profound.

At Manchester Collective our aim is to challenge and inspire our audiences, and I’m not sure I can think of three pieces that could do this any better.

Oh, Ludwig."

- Violinist, Simmy Singh

The wikipedia bit

If your appetite for information has not yet been satiated, we have some Wikipedia goodness for you in the section below. Check it out.

The Composers

The Works

Further Reading