CHRIS ALTON

Words to Grieve, Part #1

A NORTHERN VOICES COMMISSION /

IN COLLABORATION WITH EMILY SIMPSON

Responding to Manchester Collective’s music and the memories it evoked, Chris and Emily’s collaborative artwork explores bereavement, grief and language. It stems from conversations with a community of people with shared experiences, and the artists’ own reflections on society’s cultural distancing from death. The resulting six posters point towards the creation of new words and definitions – a starting point in the expansion of the vocabulary for grief.

Supported by The Granada Foundation

MEET THE ARTISTS

Chris Alton and Emily Simpson. Photography: Brandina Chisambo

Tell us about the project’s beginnings. Does music often inspire your creative process?

Chris: A number of my previous projects have been closely tied to music, such as English Disco Lovers (EDL), an anti-fascist disco group, and Under the Shade I Flourish, a rhythm 'n' blues album about tax avoidance. However, I hadn't welcomed the influence of music into my practice in a while. I really welcomed the opportunity to respond to Manchester Collective's back catalogue. It sent the project off in a really unanticipated direction.

Where does your interest in language stem from?

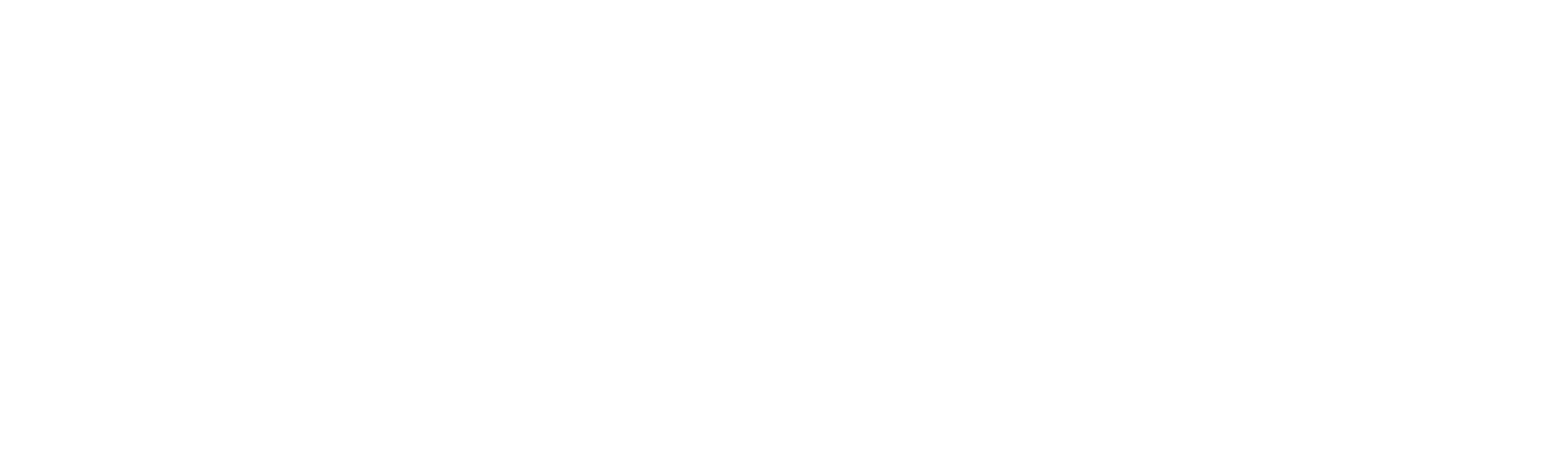

Emily: I've been working on a collection of short essays about my experience of loss, and how to build an identity as an adult without one of the biggest adults in my life – my dad. In one of the essays, I speak about how there isn't a word for someone who's lost one parent, and how not having the language to describe myself led me to feel it was a shameful thing.

Chris: Whilst ‘orphan’ can mean someone who's lost one or two parents, it's not how the word is used or understood culturally. Our conversation about this led to the idea of creating words ourselves. We wanted to broaden our vocabulary to describe our experiences.

It is difficult to verbalise complex emotions, and it becomes impossible when the words don’t even exist. Why do you think that our culture and language is so lacking when it comes to communicating grief?

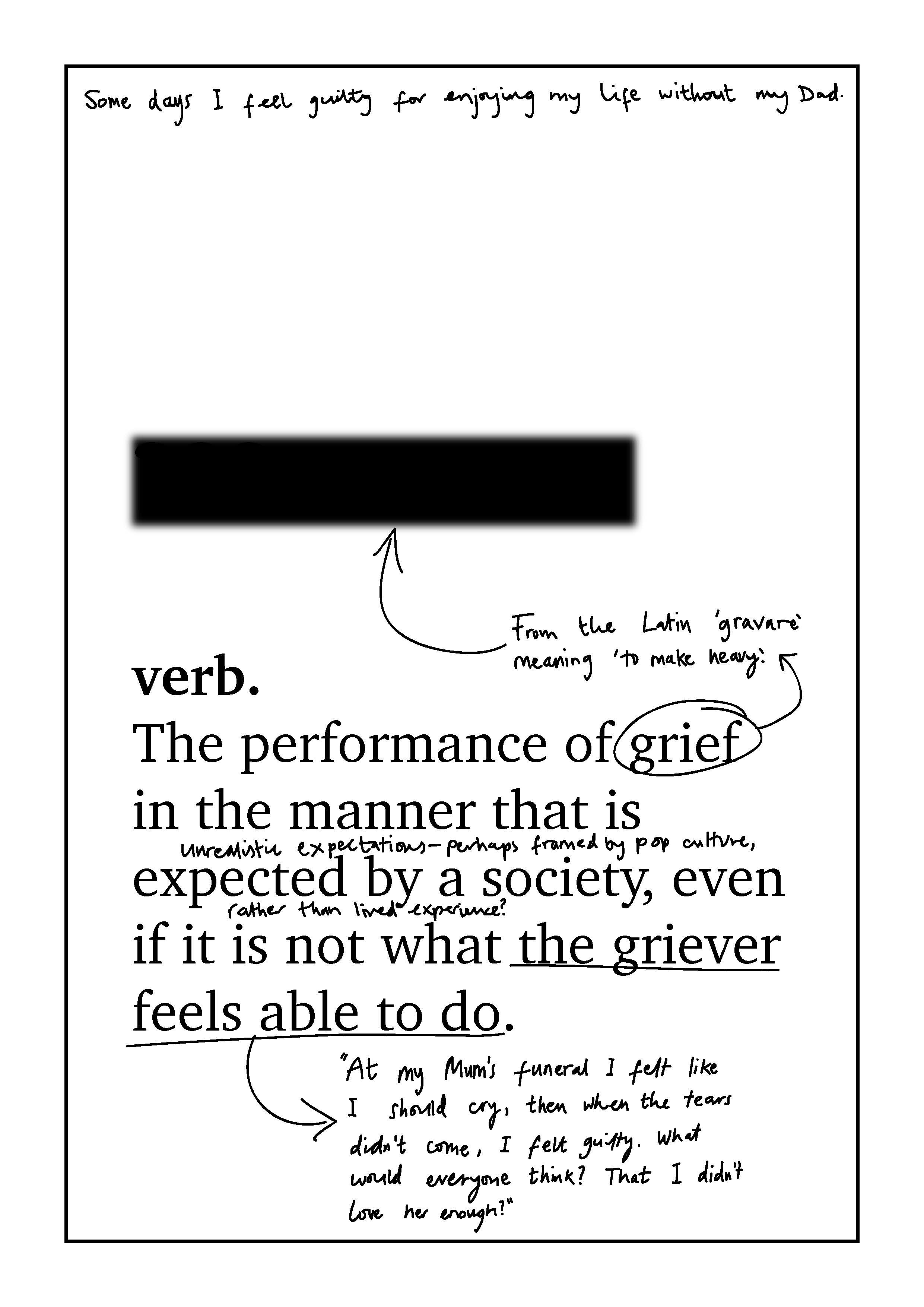

Chris and Emily: We don't know. That lack will be the result of a myriad of factors, stretched over centuries. Regardless of what caused it, when we were both bereaved in our early 20s, we each noticed the lack of words to describe our experience. We want there to be more words to offer someone than “I’m sorry”.

When you researched the vocabulary surrounding grief, were you surprised by the history of certain words?

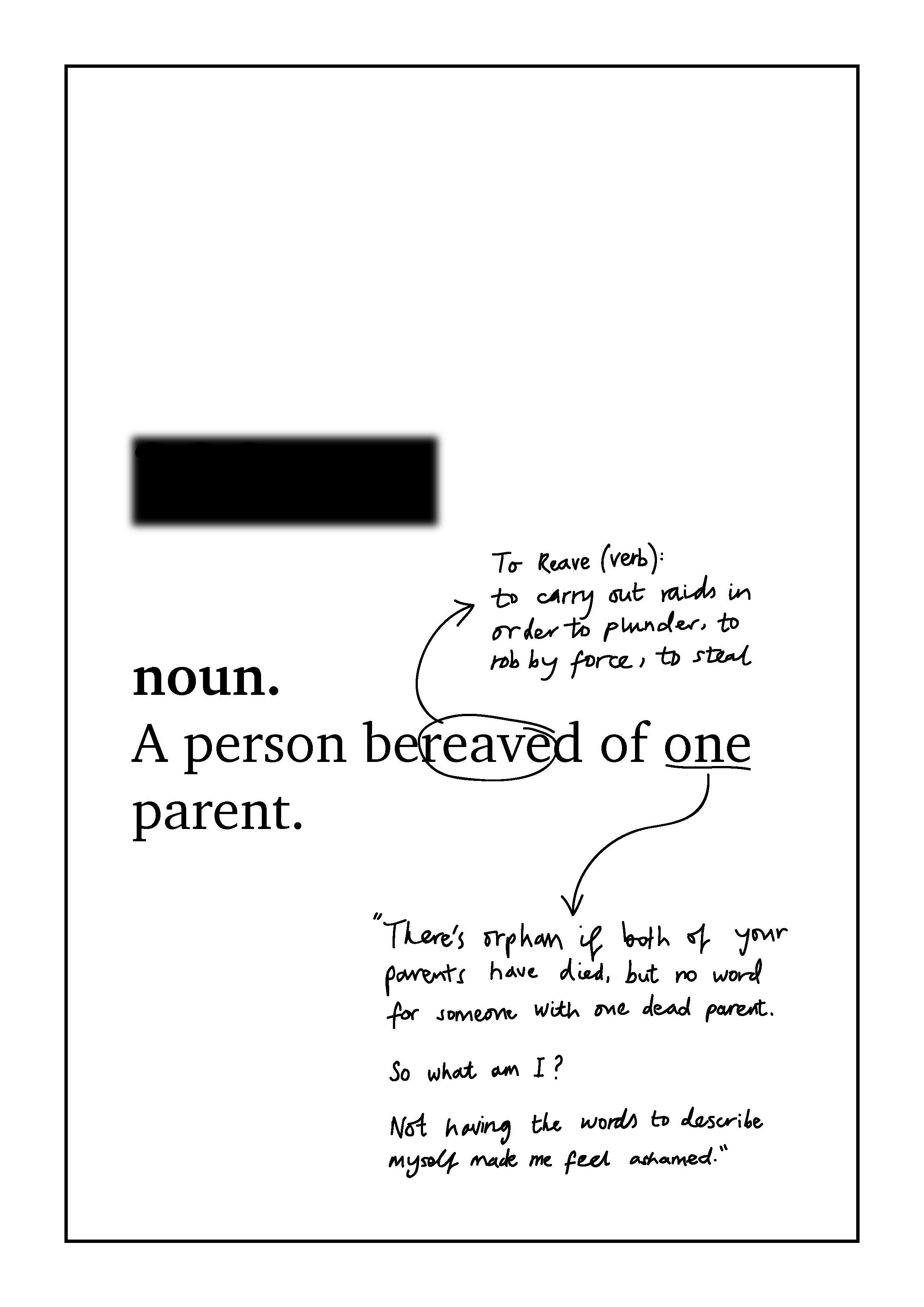

Chris: The history of a word is often hiding in plain sight. 'Bereave' is a good example of this, because the word 'reave' is right there. However, it was a surprise, because one doesn't always make that kind of connection until considering a word's root. One of the most surprising words was 'condolences' because the phrase 'my condolences' can seem so cold and formal. However, to offer someone 'condolences' essentially means that you grieve or suffer with them, which feels way more potent.

Your use of typed text and handwritten annotations is an interesting choice. What inspired your visual process?

Chris and Emily: The typed text is supposed to allude to dictionary definitions; although the words that are being defined are redacted, as they don't yet exist. Then, the annotations were a way of offering a window into our thought processes, research and personal anecdotes. We also wanted them to carry a sense of being in progress, as this work is ongoing.

Grief is such a personal but universal experience. Is there something you would want the viewers of your artwork to take from your posters?

Chris and Emily: Through our vulnerability, we hope that we're making space for others to be vulnerable. People who have experienced bereavement and grief have already commented that they recognise some of their own experiences in what we've made. Hopefully, others will feel the same. Perhaps they'll feel less alone or better equipped to speak or think about their experiences.

We also hope that people come away with the sense that language is malleable. Language shapes reality: by reshaping or augmenting language, can we reshape our cultural relationship with grief?

Do you see this as the beginning of a broader and more open discussion surrounding grief? What are your hopes for the future of this project?

Chris: Yes, absolutely. We'd like to speak with more people about their experiences of grief and bereavement. It is important that we pay those we speak to for their contributions, although we need to raise some money first! Further down the line, we're hoping to work with a linguist, so that we can develop words for the concepts that we're beginning to pin down.

Emily: One of our plans for raising funds is to make fabric patches. The patches will be a way to visualise grieving and signify this experience without words. They're like a contemporary form of mourning dress. The patch's form stems from a counselling session in which my counsellor asked me to draw my life as a circle, then my grief within it. His point was that one's grief will always be the same size, but by expanding the rest of your life it will no longer be as dominant.

Interview by Carina Simi